Modern proposals of marriage can happen anywhere: on the peak of the tallest mountain, mid-skydive from a plane or sailing down the amazon river, writes Shona Parker, historical author (her first book: How the Victorians Lived).

Prince William proposed to his wife Kate Middleton whilst on safari in Kenya and he later confessed in a television interview that he had been carrying around his mother’s very expensive and well-known engagement ring in his rucksack for three weeks whilst he waited for the right moment to drop to one knee and pop the question.

For the Victorians, however, the actual proposal of marriage was a little more down to earth. The beau, having courted his beloved and got to know her, would then seek permission from her father to make an offer of marriage. Once the father’s permission was obtained, the beau then requested an audience with his beloved, setting a date and time with her parents, who in turn would make sure their daughter was ready to receive her visitor.

Once the couple were ensconced in a room together, or off on a sedate walk around the gardens, the family waited with bated breath to celebrate and then announce the betrothal of the couple to family, friends and polite society. Up until this point, a courting couple were not knowingly left alone without a chaperone, but on proposal day and there afterwards, the betrothed couple were finally allowed some space and privacy to get to know one another.

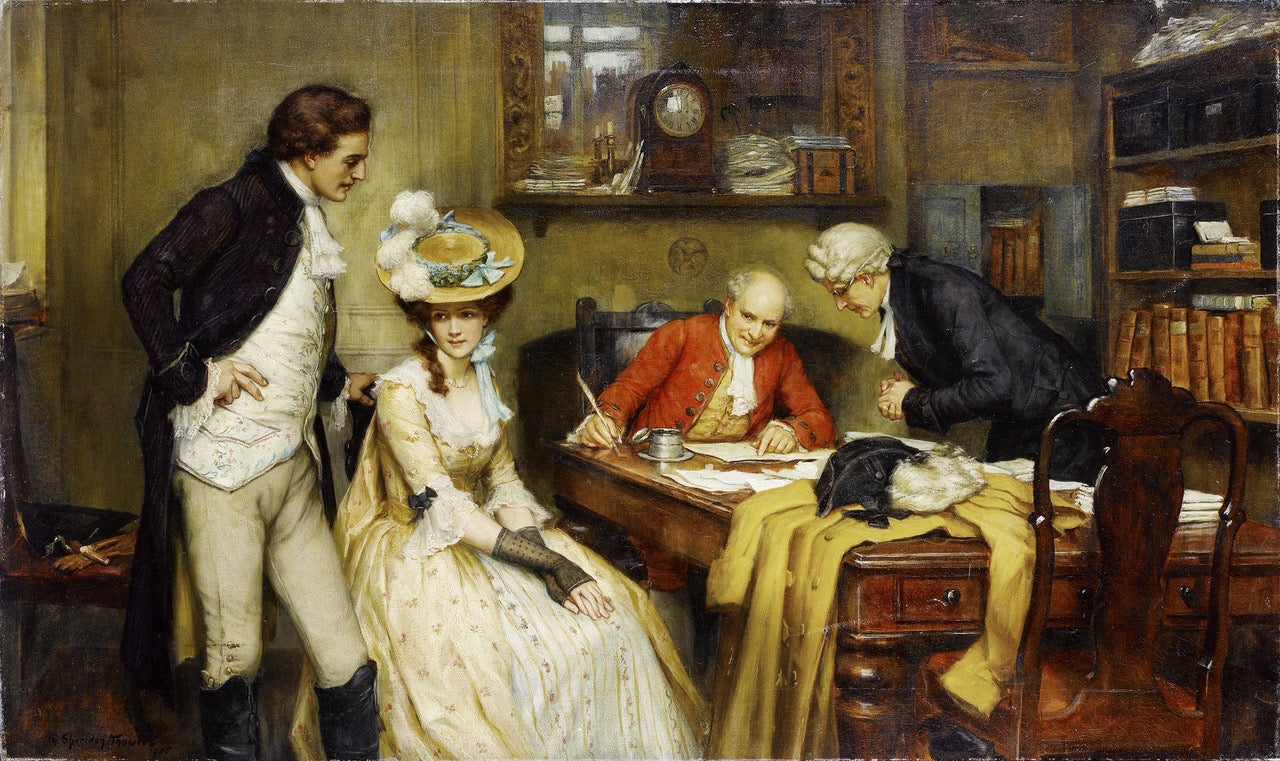

A major makes a marriage proposal to a merchant's daughter, while her family reacts with varying degrees of interest and concern.

However, the ‘traditional’ manner of the beau dropping to one knee and whipping out a jewellery box to boldly present a diamond ring whilst asking “Will you marry me?” is actually a surprisingly modern way of doing the deed.

It seems this method of proposing became popular through the silent films of the twentieth century, where showing a man on one knee at a lady’s feet whilst clutching a ring box made it easier for audiences to understand what was happening and this pose was usually used for dramatic and comedic affect.

In Charles Dicken’s Bleak House, the young, would-be lawyer Guppy’s proposal to Esther is hilarious. He downs four glasses of wine for courage, adorns a bright and cheerful buttonhole and neckerchief, espouses the virtues of his mother, falls to one knee and tells Esther, “In the mildest of language, I adore you. Would you,” says Guppy, “be so kind as to allow me (as I may say) to file a declaration – to make an offer!” Esther is quite mortified and replies, “Get up from that ridiculous position immediately sir!”

In reality, the Victorian marriage proposal usually involved two people having a serious conversation, opened by the beau paying his beloved a heap of compliments before asking her if she would do him the honour of becoming his wife.

This is where Mr. Darcy, in Pride and Prejudice, gets it so horribly wrong. Known as the ‘insult proposal’, he opens with “In vain, I have struggled. It will not do. My feelings will not be repressed.” He continues to layout Elizabeth’s flaws and insult her family but then insists that despite all the setbacks, he cannot help himself, he desires her and wants to marry her. Unsurprisingly, Elizabeth rejects his proposal telling him she wouldn’t marry him if he was the last man on earth, Darcy storms out of the room whilst Elizabeth cries for a solid half hour.

Evert Jan Boks The Marriage Proposal 1882

A young girl would have been schooled in how to graciously accept or decline a proposal of marriage, whichever class she was from. Whatever her feelings on the matter, she was expected to be poised and calm throughout, lovingly and passionately accepting the offer of marriage or kindly and politely declining it. For a few moments, the Victorian woman held all the power as her beau opened himself up and left himself vulnerable to rejection. Although the family may have agreed the match beforehand, the lady, just like Elizabeth Bennet, could – and did – say no.

Happily, Mr Darcy, is forced to retreat and seriously think about his marriage intentions. His second proposal to Elizabeth Bennet is so achingly heartfelt and seemingly out of character, he leaves her speechless before she finally gathers her wits and accepts him.

Despite the Victorian marriage proposal appearing more businesslike than modern marriage proposals, they still led to countless happy unions, as exemplified by Queen Victoria and Prince Albert with their own wondrous marriage. As Queen, Victoria was required to eschew tradition and propose to Albert; we can only assume she got it right as he readily accepted and bestowed upon her love, affection and nine children.

Towards the end of the Victorian era, many more young couples started to discuss married life together before seeking permission from the young lady’s parents. Oscar Wilde’s Lady Bracknell sums up the old way of seeking an engagement. On learning her daughter Gwendolen has taken her future into her own hands and encouraged Jack Worthing into proposing marriage already, Lady Bracknell crisply announces “Pardon me, you are not engaged to anyone. When you do become engaged to someone, I, or your father, should his health permit him, will inform you of the fact.”

Thankfully, these attitudes are now in the past. But however, and wherever it was carried out, the marriage proposal was and still is always a unique experience for each couple, full of hopeful anticipation and sheer excitement for the future.

Shona Parker is a writer of English social history. Her first book, How the Victorians Lived, is available now from history specialists Pen and Sword Books and her second will be published in 2026. You can read more of her writing on Victorian England on her blog www.backinthedayof.co.uk